Textile Mills to Mainframes

Corporate Paternalism in the Research Triangle

Work in the Idea Factory

Just before Alex Sayf Cummings published her remarkable book on the Triangle-area called Brain Magnet in 2020, I had found the histories of the area lacking and I hoped that I could better understand the place where I had grown up and as of 2016 had once again called home.[1] With the publication of Cummings work, I found a lot to be inspired by. Prior to Brain Magnet, histories of the park were largely written by its boosters without a critical eye to the idea of the idea economy. Indeed, two were published by the Research Triangle Foundation itself. The rest were a smattering of social science works measuring the success of RTP against other research parks.[2] It seemed from her work that I was on the right track. Through my own experience, observation, and study of the past, I had long believed that the Triangle’s promise of a perfect postindustrial utopia was founded on a faulty understanding of the world. Despite pretenses to moving beyond the materiality of the industrial economy, much of what has made a place like the Triangle possible is yes technology, but also a matter of geography and ideology. That is, while automation has obviously played an important role in changing the face of the American economy, just as important has been the globalization of production and trade to the benefit of capital over labor. Part of maintaining the hegemony of the global neoliberal order as it displaced the more nationally-oriented Fordist one was changing the way people thought about the world they inhabited.

Much of this ground is covered in Cummings work, but most important to the particularities of the Triangle area is a concern with the changes in the urban environment from the 1960s forward. Like many other Sunbelt cities, it is made up of several municipalities which represent different stars in a larger constellation, rather than their own distinctive city centers surrounded by suburban rings. This metropolitan sprawl which includes Raleigh, Durham, Chapel Hill, and Cary has woven hierarchies of race and class into the very fabric of the urban environment. It is looking at how these differences manifest themselves in the communities in which people live where her work is the best. This brings me to two contributions that I hope to make with my own work. With the exception of a short description of how the design of the Burroughs-Wellcome building reflected and reinforced RTP a top-down management structures and some commentary on the nature of work at SAS there is very little in the way of discussing life on the job. Another element that remains to be adequately addressed is the relationship of the Triangle to the rest of North Carolina. What happened to the rest of the state as the Triangle flourished, building itself up as a series of sprawling high-tech suburbs? These and more questions remain unanswered.

In taking up these queries, I hope to understand one of the most basic inquiries of labor history. What was life like at work for this group of workers at the workplace? What did the map of workplace hierarchy look like—not just an organizational chart, but how were distinctions acknowledged on the job in daily routines. As is so often the case, divisions can exist between employees horizontal to one another on paper, but are treated unequally in practice. á la David Montgomery, I am also interested in questions of autonomy or worker’s control on the job.[3] Which in turn poses the questions of discipline and de-skilling so brilliantly addressed by Harry Braverman around the same time.[4] In doing so, I hope to demystify the work of knowledge workers in the technology sector so important to the rise of the Research Triangle. As Philip Kraft once wrote:

Nothing is more fitting symbol of smoothly running modern capitalism than the computer. Like the market, it appears to operate independently of those who made it, and has taken on a life of its own. It is the Invisible Hand become corporeal.[5]

But as he reminds us, “computers can do nothing…unless they are told what to do and how to do it by human beings.”[6] Forgetting this fact is so crucial to the expanding post-industrial mythos that undergirds the idea of the idea economy. Even the concept of the knowledge workers is imprecise as it betrays part of my goal, which is to problematize the head and hand dichotomy that demarcates the collar-line. However, it is my contention that it does capture the importance of education and credentials to creating and reinforcing hierarchies across the workforce. By no means do I think I have come to an answer to these questions, but I think they are the right ones to grasp toward to understand not just the past but our contemporary moment. What follows is an initial, and no doubt flawed attempt at an answer through interrogating the history of one of the most important companies of the twentieth century: IBM.

Bringing a Briefcase Full of Tools:

One of the things that IBM became known for in its halcyon days was a strict adherence to a formal dress of a suit and tie. As former IBMer recalled Ed Gerlack recalled, during any customer interaction you were to “dress as a businessman.” That meant, “you would have a white shirt and tie suit and you wouldn’t look any different than a banker would look.”[7] Another former customer engineer Bruce Whistance, similarly recounted that the company used tool bags that “were made to look like businessman briefcases because IBM didn’t want it to appear that there were problems with machines not working and needed to be fixed.” That way, we would “just blend in as another white-collar executive, but we were really computer repairmen.”[8] Both of these men began their careers at IBM in the 1950s when the company was not just at the cutting-edge of technology it was practically ubiquitous with computing. Corporate strategy and image crafting aside, this incident speaks to something that goes unspoken by Gerlack and Whistance, to have a white-collar meant that worker could command at least respect regardless of renumeration or actual decision-making authority at work. This respect arose from the very old idea that being freed from the drudgery of manual labor means more time to nurture the life of the mind. In this instance, IBM was trading on this principle in its public image, even when the reality was very different.

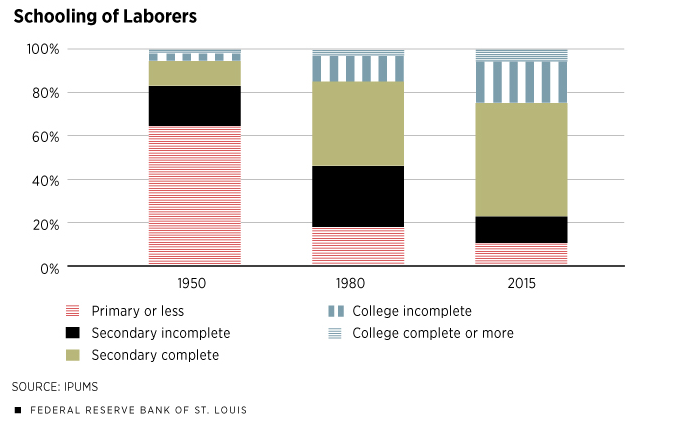

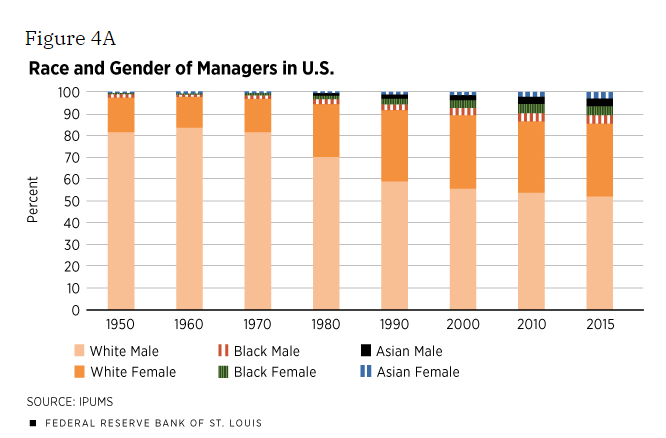

At the same time, while these customer engineers may not have lived up to their all-business image, there was in fact a major change in the composition of the American workforce underway. The numbers bear this out. Between 1950 and 1980, the amount of those who had some or had completed a degree more than doubled. While completion rates have declined since their high-point in the 1980, those who have some college has remained consistently over forty percent of the population since at least 1990. Those educated individuals have swelled the ranks of service, technical, and professional workers, while still others have rose to the ranks of management. Of even more important note, is that even those in occupations in decline like factory operatives are far more educated than they were in the immediate postwar period. Unfortunately, this further schooling was no guarantee they would keep their jobs. One ironic side effect in this shift in the workforce is that even as expectations in the broader population diminished, those professions most privileged became more diverse. So, while those more well off became more representative of the actual demographic breakdown of the country, the rest were left to fight each other for the scraps.[9]

Some were prescient enough to perceive these changes even as they were only just emerging as perceptible trends. American Marxist, autoworker, and organic intellectual James Boggs put his finger on this pulse in the1960s along with many others who were concerned with problem of automation and cybernation. Boggs wrote:

The United States has transformed itself so rapidly from an agricultural country to an industrial country, and as an industrial country has undergone such rapid industrial revolutions that the question of who is in what class becomes an even-wider and more complicated question. Today’s member of the middle class is the son or daughter of yesterday’s worker.[10]

That is, “the sons of factory workers and coal miners have become teachers, engineers, draftsmen, scientists, social workers,” and “even the radicals no longer think of their children replacing them on the assembly line,” instead they fed the “growing army of technicians and engineers who today have the same status in industry as did the plumbers, carpenters, and skilled workers in yesterday’s industries.”[11] A native son of Alabama, he paid close attention to developments in the South, pointing out that “this transformation taking place not only among whites but among Negroes,” where “men who have worked in the steel mills, on railroads, in factories, in the mines…are determined that their children will not follow in their footsteps.”[12] According to Boggs, these children were very different from their parents, not for cultural reasons, but rather because of a different relationship to work. Instead of fearing automation, they “welcome the constant changes in production as a challenge to their ability, knowledge, and ingenuity,” and further “these new workers are part and parcel of the new process of production,” where “their ideas are so crucial to the directions of the work that they are inseparable from management and the organization of work.”[13]

It was not just political radicals that observed the increasing importance of education among the working class. Blanche Scott began removing tobacco stems at just twelve years old and quit school in the eight grade to work full-time at Ligget and Meyers. Scott was able to escape the precarity of poverty through education. After working for more than twenty years in tobacco, Scott took a course to become a certified beautician, and her long career’s second act in doing hair lasted another twenty-eight. While Scott was able to take the course without completing a secondary education, she observed that the prerequisites for credentialing had become more stringent—requiring a high school diploma. She noted that “these young people today, they got a lot of things they can do now. It do require high school education,” but:

That's why I say, I hate to see a child drop out of school because if you don't finish high school, it's kind of hard. When you go to apply for a job, they're going ask you what school did you finish or what college. Then if you say, you didn't finish school, and you didn't finish high school, they might think that you ain't qualified to do much. I was so glad that I did escape by it. When I heard about, they say you had to finish high school, I went right on in there.[14]

Having had a failed first marriage and never remarrying, Scott valued her independence. Part of her dream of starting her own hair salon was so that she could own her own home. She wanted “a modern home,” and so when her ex-husband paid her a divorce settlement she gave her brother $900 dollars for a down payment for an FHA loan for her home—one that she eventually paid off in 1974.[15] However, it was not just Scott herself who was able to move up the social ladder through education, her nephew not only went on to college, but he taught for four years afterward. From there, he got “married” and “he got a good job at…IBM.”[16] Scott’s nephew was the black youth who Boggs noted was being pushed out of the very professions that had made his future possible—in this case a career as a used car salesman.

Like a Family at IBM:

While IBM was not the first company to relocate to RTP, it was certainly the company that put the project on the path to success. Before they set up shop in 1965, there was serious concerns on the part of the park’s boosters that if the tides did not change, the whole idea behind RTP would remain an unrealized plan to promote economic development. That changed when IBM took up residence. More than just a bridge between failure and success, IBM is in many ways the missing link to understanding the kind of political economy that took root in the area, not necessarily through something new, but through something very old. In her work, Cummings points to commentary that has compared SAS to a high-tech Southern mill town.[17] There is certainly something to that comparison, but I would argue that high-tech corporate paternalism made its way to the Research Triangle far before Jim Goodnight spun off his start up from his work at NC State. There is no better emblem of mid-century corporate paternalism than IBM. The Watsons created a private welfare state for its employees that kept people loyal and mostly inoculated against labor organizing. At the same time, it was not purely economic dependence on the benevolent fathers Watson and Watson Jr. that made IBM like a family for its employees.

Indeed, drawing on the work of Jacquelyn Dowd Hall Et al which described life in the Cotton Mill World, there is a sense that what they argue for life in a mill town resembles that which existed in the company towns that began to dot the landscape of upstate New York over the course of the 1940s and 50s. That is, the metaphor of family was not simply one imposed from above by an overbearing father, but one in which workers often used to explain their “relationship to one another.”[18] Some IBMers went as far as to bring their actual kin into the fold of their metaphorical family because they saw it as a place for securing the future for them. When Ed Gerlack was asked about the practice of hiring family members of those already employed, he replied that it was not just “an endorsement of the company” if “parents of a child thought enough of the company that they brought their own children to work there,” but “the best endorsement that our company could have.”[19]

For example, it was not uncommon to have fathers and sons to work with one another at IBM. In 1950, Jack Matthews was hired to work in auto fab after his stint in the Navy ended. His job consisted of running a machine that would send circuit cards down a line and he would put resistors, capacitors and other components in and solder them. Eventually Jack went on to become a mechanical engineer in the company, not before his father joined the firm at fifty years old in 1956. Having worked as a painter most of his life, Jack’s father came to IBM hoping to rest his legs after his doctor advised him not to stand on ladders anymore. Upon his father finding his way into the fold of the IBM family, Jack was inducted into what was called the Second-Generation Club for sons whose father was also an IBMer. He was given a certificate, a set of cufflinks with his father’s initials on them, along with “a gorgeous leather suitcase” with his initials engraved on it.[20] However, in the case of the Matthews family it was not just the father and son duo who were employed at IBM. After leaving the Army as a cook, Jack’s brother went on to serve in the company cafeteria at Poughkeepsie before becoming the manager of all food services in Fishkill. Later, they were joined by another of Jack’s brothers, their sister, and two of the brother’s wives. For the Matthews, working at IBM was truly a family affair.

JoAnn Cellar, another second-generation IBM employee recalled that she applied to work at the company because her father had worked at the company for a long time, and for that reason believed that since “he was happy working” that she “could be happy there as well.”[21] What’s more, JoAnn’s experience speaks to the ways in which the company culture was structured to help create a sense of community among employees. After a year into her employment editing publications for IBM Products (before eventually joining the secretarial pool), she joined what was known as the IBM Club or an organization that planned events like blood drives, wrote weekly bulletins, and hosted fun activities like bus trips for other employees. Institutions like the IBM club and places like the local company recreation center meant that IBMers interacted both in and out of the workplace on a regular basis, putting one another in the middle of both their work and home lives. While of course this by no means there was no conflict amongst employees or between rank-and-file workers and management, it certainly helped to lessen some of the worst tensions that often exist at work. The importance of family as a metaphor is clear not just in these stories of real and metaphorical kinship, but in the language of decline that is evident in most of the interviews with former IBMers. Many former employees designate the 1950s to the 1980s as a kind of golden age for the company in which they and their home and work families were taken care of.

Corporate Paternalism from Poughkeepsie to Research Triangle Park:

Before IBM decided to locate its new factory site in Poughkeepsie, the city had gained a reputation as a low-wage town. Unions dubbed it a “scab” town in the late 1920s as some manufacturers from New York City relocated there to escape union wages and contracts. So entrenched was this anti-labor orthodoxy that the Chamber of Commerce even went as far as to turn down a possibly lucrative Ford facility out of a fear that the company’s pay scale would drive up prevailing wages.[22] Even during the Great Depression, the town opted to take limited advantage of federal relief programs, despite the fact that the President himself hailed from Dutchess County. Given this legacy, it should be no surprise that the town was transformed when IBM arrived initially to manufacture munitions for the war effort in 1941.[23] Picking up the slack of state-sponsored welfare in the city, Tom Watson built housing for employees, a dining hall where employees of different collars intermingled at meals, and a recreation center that allowed IBMers to unwind together outside of work. IBM also made sure that schools could service their needs in terms of creating a pool of potential employees, while also meeting the needs of the town’s growing families. This was particularly important because while education was not initially a key into their corporate community, by the 1960s the company had largely begun to opt for credentials over internal training.[24]

Much of this should sound familiar as reasons given for why companies relocated to the South in the 1960s and 1970s. It illustrates precisely the point that many here might agree with, which is that the South has no monopoly on low wages and opposition to Unions. What made the South appealing is that it had those elements not just in quality, but in quantity.[25] However, rather than the result of some inherent Southern conservatism, it was that the South was not truly integrated into the wider national economy until after the Civil, and even then, the process was slow-going and did not really pick up in earnest until at least the 1930s.[26] An important element of Southern boosterism was the perceived need for Southern industry to play catchup in order to compete on the national market. This often led to developmental policy that put short-term needs ahead of long-term planning. Since agribusiness and extractive industry prevailed over manufacturing for the most part, Southerners often sought to shore up their economic base quickly by luring “footloose industries'' like textiles and “branch plants'' that offered “prepackaged entrepreneurial expertise and skills”[27] The assumption that selling the South on the cheap could help overcome regional backwardness helped create a paint by numbers approach to industrialization that brought companies to North Carolina that have been “largely independent of the communities in which they settled and the people they employed,” which has made it all the easier for them to “cow workers and local governments by threatening mass firings and shutdowns.”[28]

Part of the impetus behind the Research Triangle was to rethink developmental policy in order to overcome this negative feedback loop, a problem that appeared particularly acute in a state where the predominant industries were labor intensive like textiles. This meant that they were predisposed to moving over state lines in search of lower wages as competition drove down prevailing prices. Seeing that eventuality as disastrous for the state, boosters for RTP saw luring research and development facilities southward as a means of not only gaining in immediate employment numbers, but also helping to entice and develop industry though innovations made in the park. In this sense, despite some of the postindustrial pretensions of the park’s founders, ultimately much of the knowledge produced across university labs and private research facilities was to go to practical ends rather than an abstract pursuit of knowledge for knowledge’s sake. However, as Cummings takes the painstaking time to note, from the beginning the planner’s desire to keep the work of the mind separate from that of the hand was challenged by the practical need to find tenants. Early on, the plan had been to allow for no manufacturing within the bounds of RTP, but when IBM and another company Technitrol balked at that restriction, the covenant was changed to limit rather than completely eliminate it within the park’s boundaries.[29] At the same time, the work done at IBM reflected a change in manufacturing not only in the company, but across the manufacturing sector more broadly. Outside of those labor-intensive industries like textiles, furniture, and tobacco, much of the work done in manufacturing had undergone a massive transformation over course of the 1950s and 1960s. Automation had turned many workers into machine tenders.

Of course, it was not all higher pay, perks, and privileges in the IBM corporate community that created an environment in which workers were reluctant to organize. Part of this was pioneering a style of labor relations that sought to individualize the relationship of the worker to management. This included like individual performance reviews with a worker’s immediate manager that they could potentially appeal if they were unhappy with the results. Direct access to management was key to maintain a high morale—by the mid-1980s they company employed one manager for every ten to twelve employees. If that direct manager was unable to solve a worker’s problem, then the open-door policy offered an alternative solution by allowing workers to go to the next tier of management. Finally, the policy of permanent employment, which the company maintained for the first seventy-six years of its existence kept employees loyal as long as their security with the company was assured. IBM’s policy was to find workers new positions in the firm rather than fire them—something they could afford as long as they could collect monopoly rents as the company that had basically revolutionized computational technology.[30] This is not to say that there was not friction within this system of labor relations as accounts of IBM workers themselves illustrate. One employee working on one of the company’s manufacturing lines in Scotland noted that while most made about the same wage, they made “a big deal of it that that you don’t tell your mate what you’re on,” and they would “mark down what we did every day it always compared at the end of the day.”[31] It also turned out that the open-door was not so open. One employee noted that in trying to make use of the policy:

I can speak to his manager as soon as possible, but it is not going to be inside two or three days. If want to see anyone higher than that, then there’s ten days passed since the incident. That’s a filter effect…Now that’s clever.[32]

Ignoring either what was intentional misdirection from management or an example of a Kafkaesque bloated bureaucratism was easier when the company could provide security on the job and into retirement. Men like Berry Credle, an electrical engineer who moved to Chapel Hill in 1970 were able to not just live into their old age with the generous company pension program, they became important pillars of the community. In the case of Credle, helping to found the Carol Woods retirement community where he and his wife lived after he retired from almost thirty years with IBM in 1985.[33] This cradle to grave approach to corporate welfare was not to last. What Credle had taken as a given would be increasingly rarer for IBM employees after 1993.

The End of Era:

In 1993, IBM had its first “official” round of layoffs in its long history. While the company kept to the long-standing practice of either moving people to different roles internally or sending them to a new location, thousands of others found themselves out of the job. In a release to the press, the company said “while it is anticipated that some of the resource reductions will be resolved voluntarily, involuntary reductions may occur.”[34] As for the reason the company broke with tradition, a spokeswoman Joan Carl explained that , “unfortunately, in order to stay competitive in what is an extremely competitive business environment, these kinds of actions had to be taken," and "I.B.M. has tried to be as sensitive to the employees as possible."[35] It was partly this event that brought me to the Triangle in the first place. My mother was a second-generation IBMer who retained a job, but relocated southward out of fear that Dutchess and Ulster Counties was a collection of one-horse towns that would provide little in the way of a future for her young family. Part of the reason for downsizing the company’s workforce was a shift in where computers and components were manufactured, a move toward subcontracting work so that not all employee benefits would be slashed, along with competition from personal computers and network technology that meant their mainframes were becoming largely obsolete. In the case of company towns like Poughkeepsie and Kingston it was catastrophic, but in the Triangle, IBM was just another tenant of many in the park. While jobs in technology might have been safe, stable and secure manufacturing jobs like those in the furniture industry just outside the Triangle were not. The same year White’s Furniture Company, a firm in Mebane less than twenty-five miles from Durham, shuttered its doors after being open for business for 112 years.

After being laid off from White’s, Andy Foley took a job at G.E. while he took classes in criminology at a local community college in hopes of starting a career in law enforcement. For Foley, work at G.E. could not compare to his time at White’s. He recounted taking days off to go fishing and finding other ways to fill downtime at work without drawing the ire of his supervisor he called Homer, named after the famous fictional Simpsons patriarch. G.E. was different:

they fire people every day. So, you don’t really have the job security that I had at White’s. People come and go there every day where at White’s until they closed you knew basically that you had a good job.[36]

Much like those who were laid off from IBM, Foley and his coworkers lamented the end of what had in retrospect been an important time in their lives. Many of them blamed the turn of events on the changes that occurred after the company was acquired by Hickory White in 1985. From drawer builders to floor supervisors, former employees noted that the priority of the company had seemed to shift from quality and quantity, and with that change it became more and more difficult to justify the company’s traditionally high prices which more than a few workers at the factory could not afford. Some were sentimental noting the close bond between coworkers at the White’s, many others were concerned with finding a comparable job, while still others concerned themselves with finding a new career path. As an anonymous supervisor put it, “some of them is less educated than others, and the way the world’s gotten now its high tech and it’s really hard for a man to out the next morning and start looking for a job.”[37] Put another way, there was no longer a viable path like the one the anonymous supervisor took from a meat cutter at Winn Dixie to a salaried employee at White’s.

All of this highlights the continued uneven economic development between the Triangle and the rest of North Carolina. As Bryant Simon has shown through the town of Hamlet, a political economy of cheap supplanted Fordist social relations and what was left of public goods governance across the state over the course of the 1980s and 1990s. By no means did manufacturing leave North Carolina like it did in other parts of the country. In fact, by the time of the tragic but preventable fire at Imperial Food Processing that Simon’s narrative centers on, the state had become one of the most industrialized in the nation. What changed was the kinds of jobs available—lower-paid, lower-skilled, and less unionized jobs prevailed over employment that could make ends meet with a single job, let alone support a family.[38] Some of the very kinds of jobs that RTP’s founders had hoped that work in the knowledge economy would supersede. After being laid off from White’s, Annette Patterson was initially overjoyed to have found a job at A.O. Smith, but was soon out of work again after she sustained injuries due to the breakneck pace of production at the company. With bills piling up, Annette contemplated taking her own life to end the constant pressure to pay her debt. While she continued to work, nothing could provide like A.O. Smith or White’s had, because “the only thing you can find around now is fast food,” like “Burger King, McDonalds, and things like that.”[39] When she was lucky enough to find work in manufacturing it was temporary, since “temporary wants you to be without a job before they want to put you to work.”[40]

There are a few historical lessons I hope can be drawn here. The first is limits of education and professionalization to solving the problem of inequality and poverty. It can help pull a lucky few from the bottom, but it does nothing to solve underlying economic problems. Another, is that no sector of the economy is destined to stay on top forever. With those shifts, the workers in those once predominant sectors lose much of their bargaining power to command higher than prevailing wages. The example of White’s is instructive in this regard. After the company closed, what was left were the very “cheap” employers reliant on keeping their wage bill down like retail and fast food. What’s more, de-industrialization through a combination of automation and outsourcing is not just a problem for steel and automakers that many associate with the Rust Belt of the United States. As the example of IBM illustrates, lower returns have meant fewer overall jobs and a move toward a rentier business model focused more on intellectual property than actually producing physical goods. A model which has clearly definable limits as an engine for economic growth. While I’m not suggesting that the party is over by any stretch, I would like to suggest that in places like the Triangle concentrated wealth can give the appearance of progress in the face of stagnation elsewhere.[41]

[1] Alex Sayf Cummings, Brain Magnet: Research Triangle Park and the Idea of the Idea Economy (New York: Columbia University Press, 2020). The title refers to the fact that RTP was meant to reverse brain drain out of the state by keeping and drawing in new highly-skilled technical workers and professionals.

[2] Albert N. Link, A Generosity of Spirit: The Early History of Research Triangle Park (Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Foundation, 1995) and Albert N. Link, From Seed to Harvest: The Growth of the Research Triangle Park (Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Foundation, 2002). Link is currently a faculty member in the Bryan Business School whose work primarily focuses on the economics of public/private partnerships. A few other boosterish histories include: Michael I. Luger and Harvey A. Goldstein, Technology in the Garden: Research Parks and Regional Economic Development (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991) and William M. Rohe, The Research Triangle: From Tobacco Road to Global Prominence (Philadelphia: University Pennsylvania Press, 2011).

[3] David Montgomery, Worker’s Control in America: Studies in the History of Work, Technology, and Struggle, 2nd ed. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1980).

[4] Harry Braverman, Labor and Monopoly Capital: The Degradation of Work in the Twentieth Century (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1998).

[5] Philip Kraft, “The Industrialization of Computer Programming: From Programming to “Software Production,” in Andrew Zimbalist, Case Studies on the Labor Process: (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1979), 1.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Kingston-The IBM Years, Friends of Historic Kingston, “Ed Gerlack oral history interview,” New York Heritage Digital Collection, Accessed August 1, 2022, https://cdm16694.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/fhk/id/15/rec/24.

[8] Kingston-The IBM Years, Friends of Historic Kingston, “Bruce Whistance oral history interview,” New York Heritage Digital Collection, Accessed August 1, 2022, https://cdm16694.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/fhk/id/8/rec/1.

[9] Alexander Monge Naranjo and Juan I Vizcaino, “Shifting Times: Evolution of American Workplace,” Regional Economist, December 11, 2017, https://www.stlouisfed.org/publications/regional-economist/fourth-quarter-2017/evolution-american-workplace.

[10] James Boggs, The American Revolution: Pages from a Negro Worker’s Notebook (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2009), 13.

[11] Ibid., 15.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid., 35-36

[14] Interview with Blanche Scott by Beverly Jones, 11 July 1979, H-0229 in the Southern Oral History Program Collection #4007, Southern Historical Collection: Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, https://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/sohp/id/12068.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Cummings, Brain Magnet, 150-56.

[18] Jacquelyn Dowd Hall et al., Like a Family: The Making of a Southern Cotton Mill World (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1987), xvii.

[19] “Ed Gerlack oral history interview”

[20] Kingston-The IBM Years, Friends of Historic Kingston, “Jack Matthews oral history interview,” New York Heritage Digital Collection, Accessed August 4, 2022, https://cdm16694.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/fhk/id/58/rec/38.

[21] Kingston-The IBM Years, Friends of Historic Kingston, “JoAnn Cellar oral history interview,” New York Heritage Digital Collection, Accessed August 5, 2022, https://cdm16694.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/fhk/id/29/rec/27.

[22] Harvey K. Flad and Clyde Griffin, Main Street to Mainframes: Landscape and Social Change in Poughkeepsie (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2009), 144-45.

[23] Ibid., 171-73.

[24] Ibid., 176-83.

[25] Part of my intention of comparing the experience of Dutchess and Ulster Counties with the Research Triangle is to show historical commonalities shared across communities in both the North and the South. Here I am influenced the recent attempt to rethink Southern history outlined by the various historians involved with Matthew D. Lassiter and Joseph Crespino, The Myth of Southern Exceptionalism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010).

[26] Gavin Wright, Old South, New South: Revolutions in the Southern Economy since the Civil War (New York: Basic Books, 1986).

[27] David L. Carlton, “The Revolution from Above: The National Market and the Beginnings of Industrialization in North Carolina,” The Journal of American History 77, no. 2 (1990): 445–75, https://doi.org/10.2307/2079179, 473.

[28] Ibid. James C. Cobb, The Selling of the South: The Southern Crusade for Industrial Development, 2nd ed. (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1993) remains the seminal text on Southern boosterism, though he may have been overly optimistic about the potential of RTP.

[29] Cummings, Brain Magnet, 68-71.

[30] T. Dickson et al., “BIG BLUE AND THE UNIONS: IBM, INDIVIDUALISM AND TRADE UNION STRATEGY,” Work, Employment & Society 2, no. 4 (1988): 506–20, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23746627, 508-09.

[31] Ibid., 515.

[32] Ibid., 516.

[33]Interview with Berry Credle by Walter Stults. 24 October 1998. R-0073 in the Southern Oral History Program Collection #4007. Southern Historical Collection: Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. https://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/sohp/id/16045.

[34] Reuters, “First Layoffs Seen at I.B.M.,” The New York Times, February 16, 1993, sec. Business, https://www.nytimes.com/1993/02/16/business/first-layoffs-seen-at-ibm.html.

[35] Jacques Steinberg, “Among the First to Fall at I.B.M.; Thousands in Hudson Valley Told They Are Out of Work,” The New York Times, March 31, 1993, sec. New York, https://www.nytimes.com/1993/03/31/nyregion/among-first-fall-ibm-thousands-hudson-valley-told-they-are-work.html.

[36] Interview with Andy K. Foley by Jefferson R. Cowie. 18 May 1994. K-0095 in the Southern Oral History Program Collection #4007. Southern Historical Collection: Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. https://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/sohp/id/12850.

[37] Interview with Anonymous by Patrick Huber, 2 November 1994, K-0085 in the Southern Oral History Program Collection #4007, Southern Historical Collection: Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. https://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/sohp/id/13799.

[38] Bryant Simon, The Hamlet Fire: A Tragic Story of Cheap Food, Cheap Government, and Cheap Lives (New York: The New Press, 2017).

[39] Interview with Annette F. Patterson by William Bamberger, 18 June 1995. K-0105 in the Southern Oral History Program Collection #4007, Southern Historical Collection: Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. https://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/sohp/id/15254.

[40] Ibid.

[41] I find the work of Aaron Benanav in Automation and the Future of Work (New York: Verso, 2020) to be incredibly compelling in illustrating just this point. His argument can be boiled down to that so far, the search to find an economic engine as effective as manufacturing have produced very little in the way of tangible results. This is due partly to the difficulty in automating sectors like service that for right now employ a significant portion of the workforce